Filling in For History: Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper, and The Pride of the Yankees

Is it Opening Day yet?

Lou, what else can I say, except that it was a sad day in the life of everybody who knew you when you came into my hotel room that day in Detroit and told me you were quitting as a ballplayer because you felt yourself a hindrance to the team. My God, man, you were never that. - Joe McCarthy, New York Yankees’ manager, 1939

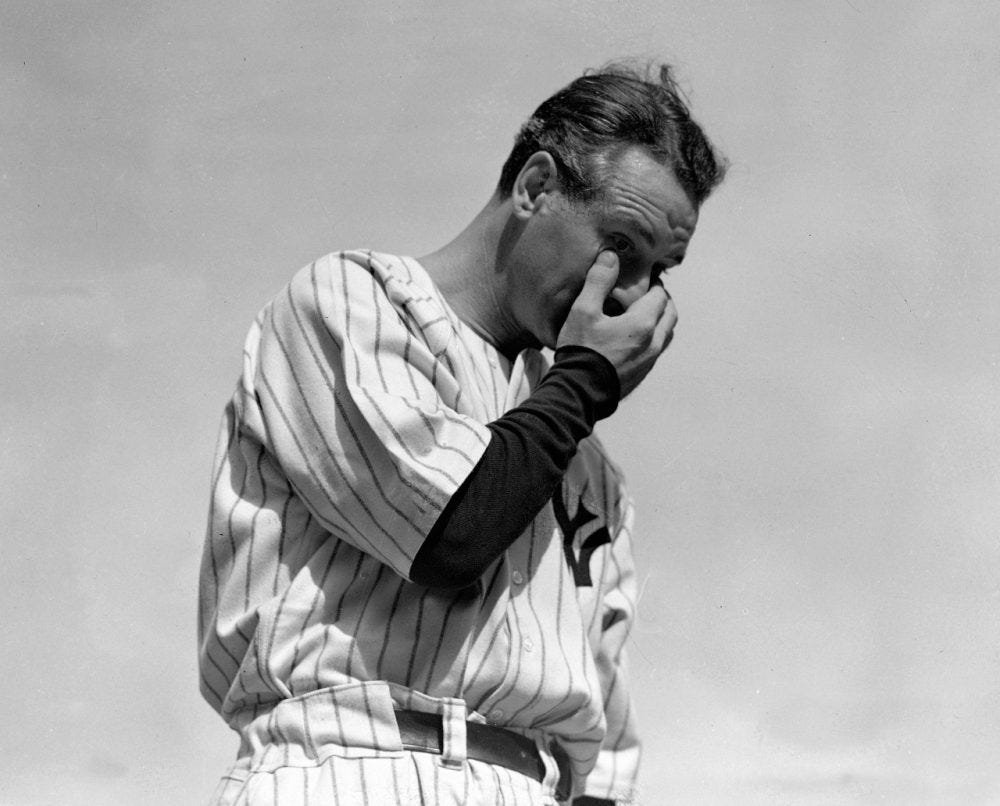

In June of 1939, New York Yankees’ beloved first baseman, Lou Gehrig, announced his retirement from baseball. The idea that the Yankees would lose Gehrig, affectionately nicknamed “The Iron Horse,” a moniker honoring his unwavering dedication to his team, fans, and the sport, was unfathomable. In many ways, Gehrig was the heart and soul of the team—and the entire league, really. By all accounts, he was a decent, upstanding guy, and a damn good ballplayer, too. Over the course of his fourteen years with the Yankees, Gehrig appeared in 2,130 consecutive games, breaking the previous record set by famed shortstop Everett Scott (1,307 games) in 1933. (This would stand for 56 years until 1995 when Cal Ripken Jr., the current record holder, surpassed Gehrig’s seemingly unbreakable record.) And throughout those 2,130 games, Gehrig played with broken bones and concussions, aching muscles and fevers. Nothing stopped him. He was the ideal baseball player, and every manager’s dream, with a perfect combination of talent, strength, and humility. Quitting was not in that man’s vocabulary, and his perseverance was an inspiration. Even in his slump, beginning in the 1938 season (and an inevitability in even the best baseball player’s career), Gehrig pushed himself even harder. And despite growing fatigue and a noticeable change in his legendary strong, left-handed swing, Gehrig maintained his poise and leadership on the team, while his teammates and fans remained hopeful of a triumphant return to form for The Iron Horse. But Gehrig’s strength and work ethic were no match for the deadly disease which was silently, but quickly destroying his body. On May 2, 1939, Lou Gehrig’s consecutive game streak came to an end as he pulled himself from the starting lineup and watched from the dugout. The next day he wrote the following to his wife, Eleanor:

I broke just before the game because of thoughts of you -- not because I didn't know you are the bravest kind of partner, but because my inferiority grabbed me and made me wonder and ponder if I could possibly prove myself worthy of you.

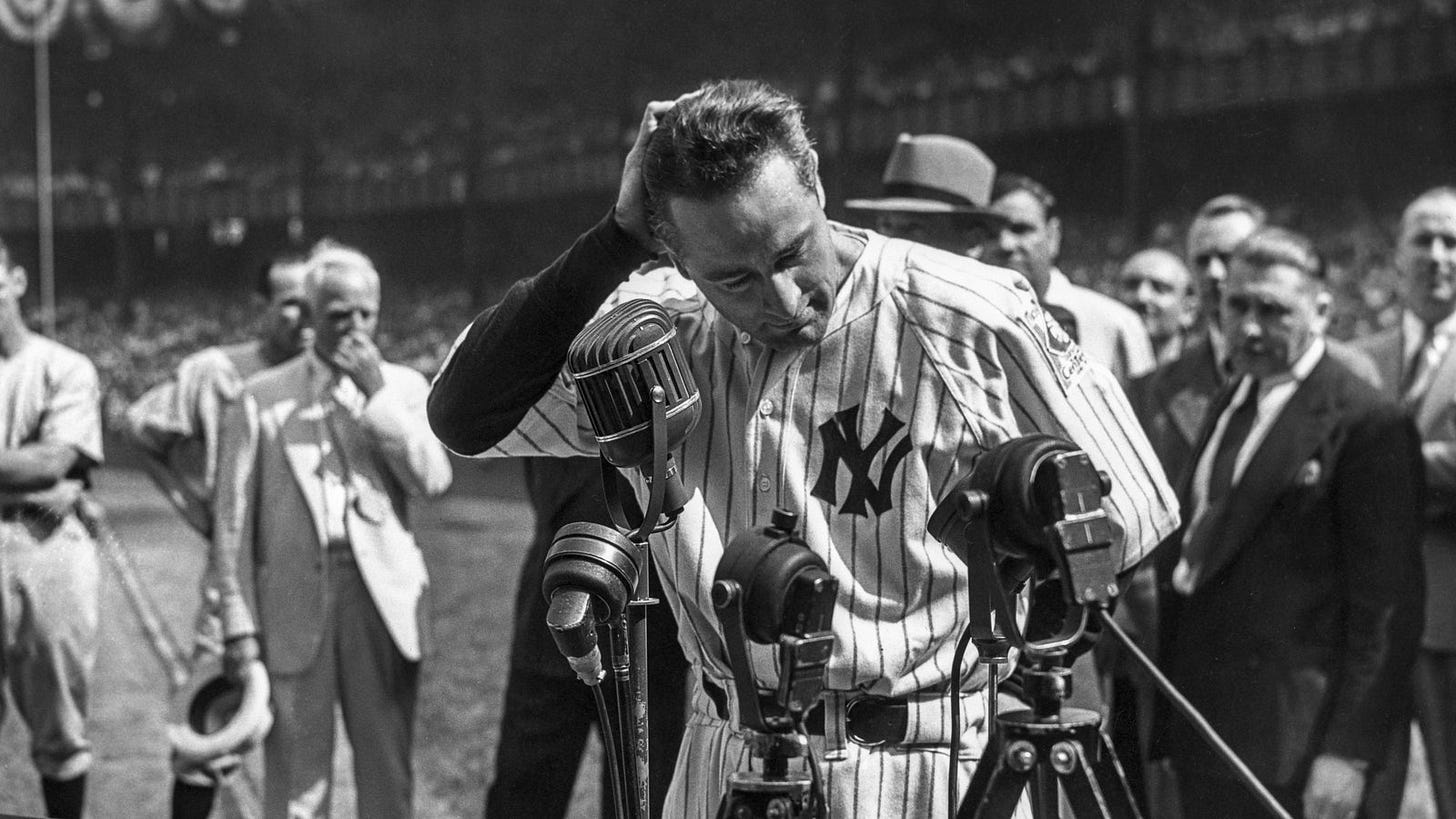

On July 4, 1939, a couple weeks after his retirement and illness (the fatal neurological disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [ALS]) were made public, the New York Yankees designated it “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day.” In an emotional ceremony between the two games of a doubleheader, manager Joe McCarthy, along with teammates past and present, including the great Babe Ruth, and even Yankees’ staff, honored Gehrig with speeches, trophies, and other meaningful gifts. Gehrig, dressed in his uniform one last time, remained stoic as he fought back tears and struggled to stand due to the disease that was ravaging his body. At the urging of the audience, and with a little encouragement from Joe McCarthy, a humble and visibly moved Lou Gehrig stepped up to the microphone and addressed the crowd at Yankee Stadium with what is now known as his famous “Luckiest Man” speech. On June 2, 1941, two years after his speech, Gehrig succumbed to his illness. And within weeks of his death, movie studios in Hollywood began courting Gehrig’s widow, Eleanor, for the filming rights to his story. After negotiations with major studios, including MGM, Eleanor Gehrig accepted an offer from Samuel Goldwyn.

In the book The Pride of the Yankees: Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper, and the Making of a Classic, author Richard Sandomir gives a thorough and entertaining account of Goldwyn’s production of The Pride of the Yankees (1942). Initially, Goldwyn wasn’t at all interested in Gehrig’s story, until he was convinced to watch a newsreel of the appreciation ceremony, which only featured a small snippet of Gehrig’s speech. The notoriously cranky Goldwyn was moved to tears by what he saw, confirming that he was, in fact, human. Goldwyn was not only affected by this moment, but saw the opportunity to make a great film about a beloved, tragic American hero. Under Goldwyn’s watchful eye, director Sam Wood, along with screenwriters Herman J. Mankiewicz and Jo Swerling, made a film worthy of Gehrig’s remarkable story, despite the usual flourishes and exaggerations which often plague the Hollywood biopic. But it wasn’t just about adapting a compelling story for the screen. There was a real sense of obligation and responsibility to Gehrig’s legacy, and more importantly, creating a surrogate account of that final speech for which there was no complete footage. The story behind the speech is almost as legendary as the speech itself, and there has been much debate as to who wrote it and how it came about, especially since there was no record, written or otherwise. But Eleanor Gehrig insisted that she knew the speech from memory, as she and Lou had written it together. Her version is what appears in the film and has melded with the limited taped footage available, as well as various accounts from those who were in attendance, to create a full retelling of that moment in history.

With the death of Lou Gehrig fresh on the minds of many Americans, the search for an actor to portray him was of national interest. Although many names were tossed around for the role, including Eddie Albert, Cary Grant, Pat O’Brien, and Spencer Tracy, the only one that really made sense was Gary Cooper. Of course, the “search” for the actor was a publicist’s dream, and combined with Gehrig’s popularity and his recent cultural imprint, it created a heightened interest in the production.

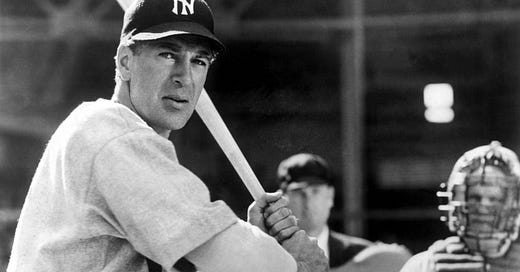

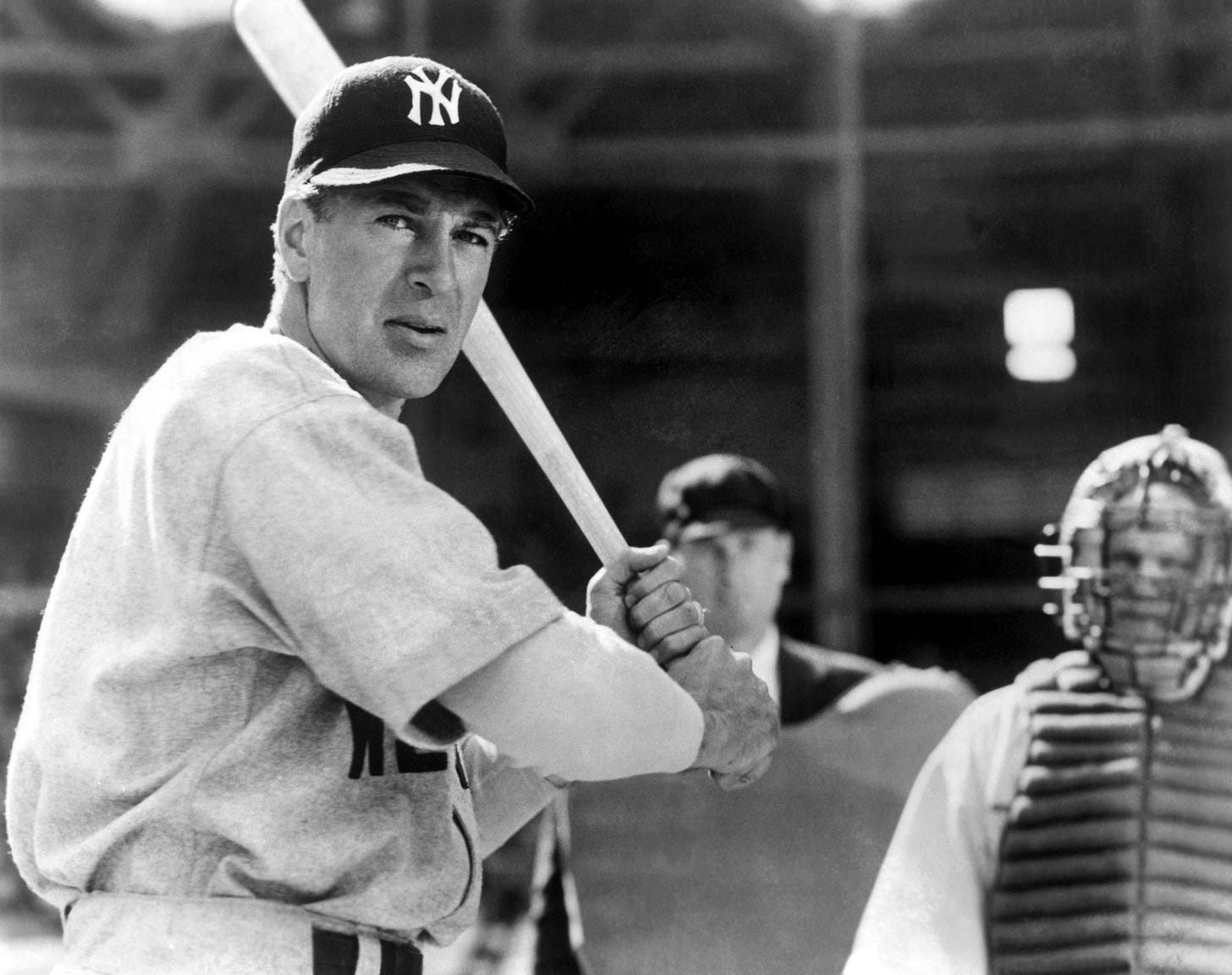

While Gary Cooper was obviously the best choice to play Gehrig in terms of look and stature, he knew absolutely nothing about playing baseball. He couldn’t throw a ball or swing a bat convincingly, which was only complicated further by the fact that he wasn’t left-handed like Gehrig. Not only did Coop have to learn how to play ball as a lefty, he had to change small things, like how he smoked and how he gestured. Cooper spent six weeks during pre-production working with ball player Lefty O’Doul. This kind of training for a role wasn’t terribly common in studio-era Hollywood, which made the production even more special. Under the instruction of O’Doul, Cooper practiced his batting technique by swinging an axe with his left hand, until he could produce a decent, convincing swing for the cameras. But his throwing was an entirely different problem. Of his ball-throwing skills, O’Doul apparently said to Cooper, “You throw a ball like an old woman tossing a hot biscuit.” Fortunately, Cooper’s double, Babe Herman, provided many of the more athletic moments that were outside of Cooper’s limited baseball skill set. For years it was rumored that Sam Wood and cinematographer Rudolph Maté, along with set designer William Cameron Menzies, worked to reverse the film negatives to make the right-handed Cooper appear to do everything in the correct left-handed manner. While certainly plausible, it would be unnecessarily complicated. And while there is some proof of reversed images in one key sequence in the film, the theory was debunked in 2013 by an expert at the Baseball Hall of Fame, and confirmed by Richard Sandomir in his book.

On the heels of his Academy Award winning performance in Howard Hawks’s 1941 biopic Sergeant York, based on the inspirational true story of World War I hero Alvin York, Gary Cooper seamlessly transitions into the role of another American hero, albeit of a different sort, with effortless precision and charm. Cooper wasn’t an explosive actor like Spencer Tracy, James Cagney, or even Cary Grant. He had a quietness about him, a calculated stillness, that is sometimes mistakenly dubbed as “wooden.” There’s nothing wooden about Coop; he’s the embodiment of a restrained masculinity that no one has been able to replicate. No one. Cooper as Gehrig was as natural as Cooper as Alvin York. Or Cooper as John Doe. Or Cooper as Marshal Will Kane. There’s no denying he’s Gary Cooper playing these real figures and fictional characters—meaning that he didn’t completely disappear into a role. You know it’s Coop up there on the screen. But he brought a special Coop-exclusive subtlety to every role. Seriously, pay attention the next time you watch one of his films. You’ll come away with a newfound appreciation of his talent as an actor.

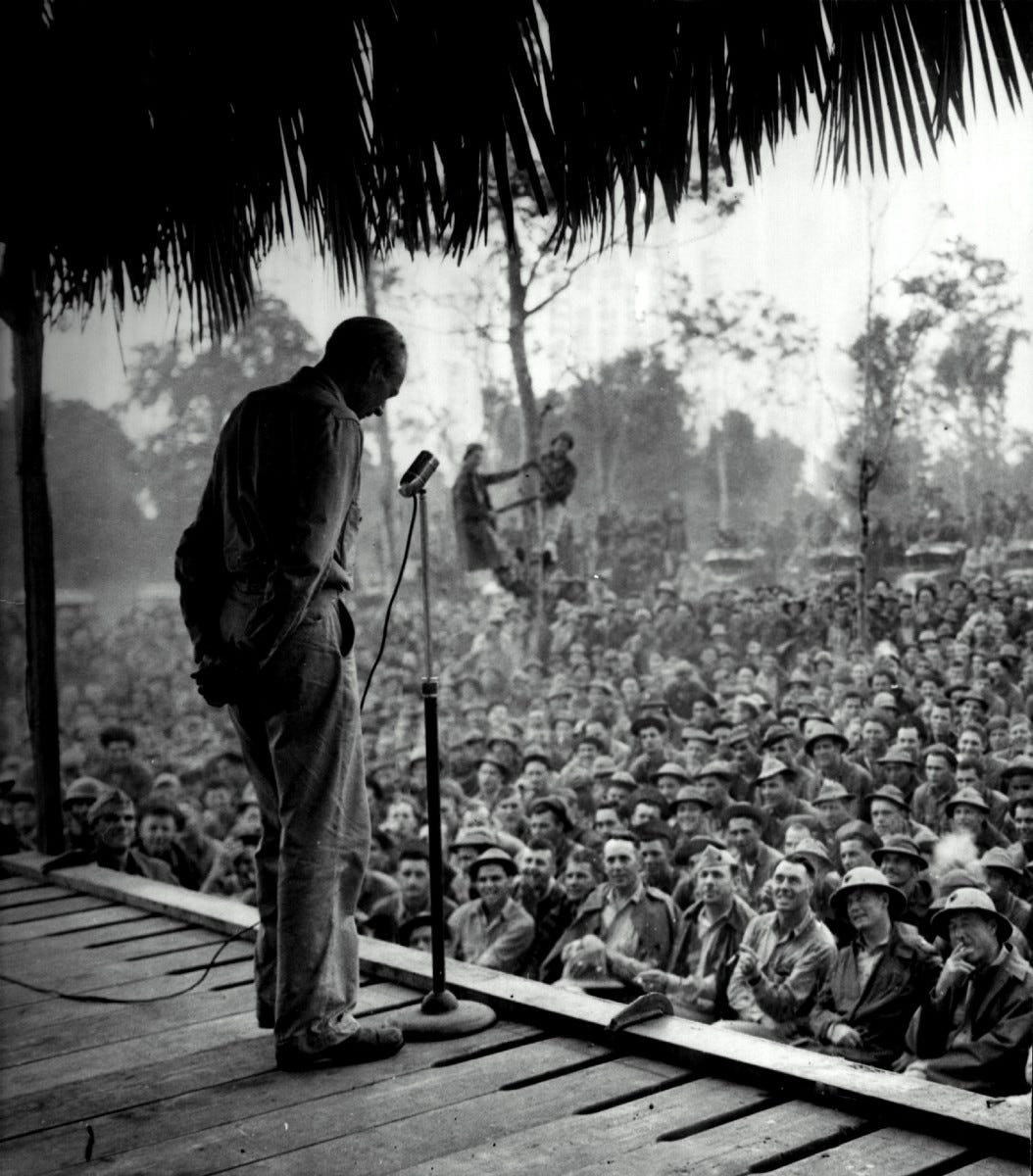

Outside of his performance in The Pride of the Yankees, many Americans looked to Cooper as a living extension of Gehrig’s spirit. When on tour for the USO during World War II, soldiers in the audience requested he recite the speech from The Pride of the Yankees. Cooper obliged, of course. When he agreed to portray Gehrig, Coop knew he was taking on a huge responsibility, and he was honored to do so. As for the role of Lou Gehrig’s wife, Eleanor, Samuel Goldwyn looked no further than the endearing and utterly delightful Teresa Wright, a favorite among fans of classic film. The Pride of the Yankees was only her third film, but Wright had already reached a level of success that takes some actors a lifetime to achieve. The young actress was nominated twice for the Academy Award for her work in two films directed by William Wyler: 1941’s The Little Foxes and Mrs. Miniver in 1942, which earned her the award for Best Supporting Actress. Portraying a living person can be challenging, but Wright was up to the task, creating a strong, sympathetic companion to Cooper’s Gehrig, despite being significantly younger and less experienced than her leading man. Both Wright and Cooper were nominated for their performances in the film.

While there are minor inaccuracies to The Pride of the Yankees, the film is a loving, sentimental tribute to one of the great sports legends of all time. In the 75 years since the film’s release, its moving final sequence has become the definitive account of that most special afternoon in Yankee Stadium.